The Lady From Shanghai

Director: Orson Welles| Producer: Orson Welles, Richard Wilson and William Castle| Screenplay: Orson Welles | Cinematographer: Charles Lawton Jr.| Country of Origin: USA | Year: 1948 | Running Time: 86-87 min.

Principal Cast: Rita Hayworth, Orson Welles, Everett Sloane, Glenn Anders

By 1946, Orson Welles had found he was no longer welcome in Hollywood. The once-promising director had made and released two unsuccessful films in succession: Citizen Kane (1941, a film that was nearly destroyed for its thinly disguised depiction of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). As a result Welles was considered unbankable by studio heads. Welles would not return to Hollywood filmmaking until 1947’s The Lady from Shanghai.

Before becoming a filmmaker Orson Welles had carved out a considerable reputation for himself in theatrical and radio productions. By the age of eighteen he was a successful actor at the Gate Theatre in Ireland and a year later, he made his Broadway debut as Tybalt in Romeo and Juliet. Welles’ collaborations with director/producer John Houseman (including the staging of an all-black ‘voodoo’ Macbeth), led the two to form their own repertory company, the Mercury Theatre.

Welles was soon directing the Mercury players in weekly, hour-long radio dramas for CBS. He exploited radio’s intimacy to heighten the sense of narrative immediacy. One especially infamous production being his notorious Halloween 1938 broadcast of H.G. Wells’ novel War of the Worlds (1898). This production used concocted news bulletins and eyewitness accounts that were so seemingly authentic in their reportage of hostile Martians landing in New Jersey that a panic ensued among unsuspecting listeners. Soon after this innovative media success, RKO brought Welles to Hollywood to produce, direct, write and act in two films. The studio paid him $225,000 plus total creative freedom and a percentage of the profits. This deal was the most generous offer a Hollywood studio had ever made to a largely untested filmmaker. His first film, Citizen Kane, described today as the most stunning debut in the history of film, fared poorly at the box office. When his second film, The Magnificent Ambersons was also a commercial failure Welles found himself dismissed from his contract with RKO.

After leaving Hollywood, Welles returned to the theater world, a move that eventually led him from New York back to California. In 1946 while working on a stage adaptation of Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days, he ran out of money. To obtain the necessary funding to finish the project Welles put in a call to Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn, and offered to write and direct a picture for $50,000. As Welles told the story the conversation went:

I called Harry Cohn [head of Columbia Studios] in Hollywood and I said, ‘I have a great story for you if you could send me $50,000 by telegram in one hour. I’ll sign a contract to make it.’ ‘What story?’ Cohn said. I was calling from a pay phone, and next to it was a display of paperbacks and I gave him the title of one of them, Lady from Shanghai. I said, ‘Buy the novel and I’ll make the film.’ An hour later, we got the money.”

While Cohn did agree, he stipulated that he would only send the money if Welles would direct the movie free of charge. Although the funds were not enough to save the stage production (which closed after a very short run), Welles soon found himself at the helm of The Lady from Shanghai. Reportedly, when Welles finally read the book he thought it was horrible. He then set about writing the adaptation in three days.

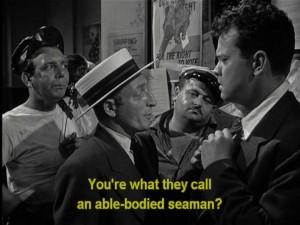

As experimental and groundbreaking as Kane, Welles conceived a vision of the film as “something off-center, queer, strange.” He cast himself in the male lead and brought in some of his colleagues from the Mercury Theater for the other roles–most notably his casting of Everett Sloane as the crippled, shifty lawyer Arthur Bannister. The part of femme fatale Elsa Bannister was originally intended for French actress Barbara Laage (who had yet to make her first film appearance) however, Cohn stepped in and decreed the lead would go to Rita Hayworth, Columbia’s biggest star. Welles and Hayworth, who had married in 1943, were officially separated at the time and Hayworth agreed to play the role as an attempt to reconcile their marriage. Though her plan worked temporarily, ultimately the two divorced before the film was finally released.

The first thing Welles did at the start of production was to order Hayworth’s trademark long, luscious red hair bobbed and dyed blonde, an act that did not impress his bosses at Columbia. who were hoping the appeal of Hayworth’s star image, which had been carefully built up in films such as Gilda (1946) would bring people to the theatre. Harry Cohn was later quoted:””The six people who saw what Orson Welles did to Rita wanted to kill him, but they had to get behind me in line.”

The Mexico shoot was plagued by a number of problems, many of them detailed by producer William Castle in his diary. During the day, the temperature was usually blisteringly hot, and at least once, Hayworth collapsed from the heat. At night, millions of poisonous insects swarmed around the arc lights, often blotting them out. Some scenes were filmed close to a crocodile-infested river and the rock from which Hayworth’s character dives into the ocean had to be scraped to remove poisonous barnacles. A substantial delay in shooting occurred when Welles was bitten and his eye swollen shut to almost three times its normal size.

Shooting was also delayed whenever Errol Flynn, who owned the yacht on which much of the action takes place. disappeared for extended lengths of time. He skippered the yacht in between takes, and his contract stipulated the yacht could not be used unless he was present.

The initial rough cut of the film ran approximately 155 minutes. After testing poorly with preview audiences, editor Viola Lawrence was brought in to cut out over an hour of footage, bringing the film to its current length of 87 minutes. While Welles was unhappy with many of the cuts (more specifically those Lawrence made to the Chinese opera and Funhouse sequences), he objected even more strongly to the studio’s choices for score and sound design.

For many years The Lady from Shanghai was considered one of Welles’ greatest failures. However, contemporary audiences and scholars alike agree that the film is a well-acted and stylish example of the film noir in which the performances of Hayworth, Sloane and Anders in particular stand out. The film’s visually striking deep-focus and chiaroscuro cinematography along with a number of other offbeat touches characterize The Lady From Shanghai as a film that only an immensely talented and innovative director like Welles could have produced.

Some Interesting Trivia:

Errol Flynn can also be seen in the background in one scene outside a cantina. Apparently when an assistant cameraman, suddenly dropped dead of a heart attack, the often-drunk Flynn tried to put him into a duffel bag, and Welles had to immediately send someone ashore to alert authorities before Flynn could bury the man at sea.

The color used to dye Rita Hayworth’s hair was called “topaz blonde”

Orson Welles was very displeased with the score put together by the studio appointed composer. In particular, the final mirror scene was supposed to be unscored – to create the sense of terror.

The film has often been interpreted as a commentary on the doomed marriage between Hayworth and Welles.

Near the end of shooting, Orson Welles told Columbia executives that he wanted a complete set repainted on a Saturday for shooting on Monday. After Columbia exec Jack Fier refused (stating union rules and the expense of calling in a crew of painters to work on a weekend) Welles and several friends broke into the paint department that Saturday and repainted the set themselves. When they were finished they hung a banner on the set that read “The Only Thing We Have to Fear is Fier Himself”. On Monday, when the union painters arrived at work and saw that the set had been repainted by someone else, they refused to work and threatened to stay on strike until a union crew was paid triple time for the work that had been done. To placate the union, Fier agreed to pay them what they wanted but put the cost on Welles’ personal bill. In addition, he had the union painters paint a banner saying “All’s Well That Ends Welles”.

For Further Reading:

Welles, Orson and Peter Bogdanovich. This Is Orson Welles. Ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum. Da Capo Press, 1998.

Telotte, J. P. “Narration, Desire, and a Lady from Shanghai.” South Atlantic Review, 49.1. Jan. 1984. 56-71.