Archive

Pretty Woman

Production Credits:

Director: Garry Marshall | Producer: Arnon Milchan, Steven Reuther, Gary W. Goldstein | Screenplay: J.F. Lawton | Cinematography: Charles Minsky | Country of Origin: USA | Year: 1990| Running Time: 119 min

Principal Cast: Richard Gere, Julia Roberts, Hector Elizondo, Jason Alexander, Laura San Giacomo

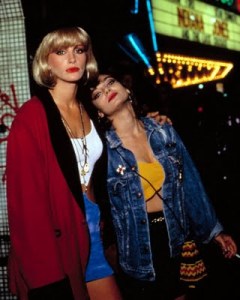

In 1990, Disney released a modern-day version of the Cinderella story. Or more accurately a Cinderella story with a twist for in Pretty Woman, Prince Charming is a businessman and Cinderella is a street walker. Originally intended to be a serious drama, the film was later re-conceived as romantic comedy with a large budget. Widely successful at the box office, it became one of the highest moneymakers of 1990 establishing Julia Roberts as a star overnight.

Pretty Woman was initially conceived to be a dark story about prostitution in New York City in the late 1980s. The relationship between Vivian and Edward also originally harboured controversial themes, including the concept of having Vivian addicted to drugs; part of the deal was that she had to stay off cocaine for a week, because she needed the money to go to Disneyland. Edward eventually throws her out of his car and drives off. The movie was scripted to end with Vivian and her prostitute friend on the bus to Disneyland. Roberts would later describe the original script as

“a really dark and depressing, horrible, terrible story about two horrible people and my character was this drug addict, a bad-tempered, foulmouthed, ill-humored, poorly educated hooker who had this weeklong experience with a foulmouthed, ill-tempered, bad-humored, very wealthy, handsome but horrible man and it was just a grisly, ugly story about these two people.”

The original script was bought by Vestron Pictures to be shot as a low-budget film. When Vestron went out of business, producers Steve Reuther and Arnon Milchan got involved and managed to gain the interest both Universal and Touchstone Films (a division of Disney). After a bidding war, the rights to 3000 were eventually sold to Touchstone for $17 million. When Touchtone took over production, the film found a new director in Garry Marshall, who was admittedly nervous about taking on the

project. Executives at Disney wanted to lighten-up the subject matter and screenwriter Lawton was asked to do another draft of the script. As he later remembered “I did two drafts that made it more of a love story – they got together at the end. I took out the fact that he had a girlfriend he was cheating on with her and a few other things, and Disney’s reaction was that I’d gone too far, lightened it up too much.” In all the script would go through six drafts by several writers. One example of the changed plotline occurs when a suspicious Edward breaks into the bathroom to find Vivian flossing her teeth instead of doing drugs as he had feared. In the original script she was doing drugs.

Casting of Pretty Woman was a rather lengthy process. For the lead role of Vivian, director Garry Marshall originally envisioned Karen Allen or Mary Steenburgen. Meg Ryan was also a top choice of Marshall’s, but all turned him down. The part then went to many better-known actresses of the time including Michelle Pfeiffer, Darryl Hannah and Molly Ringwald, who turned it down because she felt uncomfortable with the content in the script, and did not like the idea of playing a prostitute. Ringwald has since stated in several interviews that she regrets the decision. Winona

Ryder, who was a popular box-office draw at the time, was considered, and auditioned, but turned down because Marshall felt she was “too young”; as was Jennifer Connelly. When all the other actresses turned down the role, 21-year-old Julia Roberts, a relative unknown at the time, with the exception of her Oscar nominated performance in the film Steel Magnolias, won the part. Her performance would make her a star.

For the male lead, Marshall had initially considered Christopher Reeve and John Travolta. Al Pacino was also in the running, going as far as doing a casting reading with Roberts before turning the leading role down. Richard Gere was suggested early on, but Gere who had read 3000 and rejected it. It took a trip from Roberts and Marshall to Gere’s apartment in New York to persuade him before he finally agreed to

the project.

Principal photography commenced on July 24, 1989 and was completed on October 18, 1989. Filming locations included the Regent Beverly Wilshire hotel on Rodeo Drive (which was the only hotel that would allow its exterior and lobby to be filmed), the former Ambassador Hotel, and various sites in San Francisco, including the War Memorial Opera House. Sets were built in Burbank to double as the hotel rooms and Edward’s office. Filming was generally pleasurable and easy-going experience for those involved, the films budget was broad and the shooting schedule was flexible. Filmmakers did face issues when it came to the car that Lewis drove as both Ferrari and Porsche had declined the product placement opportunity of the car Edward drove, because the manufacturers did not want to be associated with soliciting prostitutes. Fortunately Lotus Cars saw the placement value with such a major feature film and supplied a Silver 1989.5 Esprit SE, a smart move by the company as the sales of the Lotus Esprit tripled during 1990-91.

There are several interesting stories from the production of the film such as the well-known story of the scene in which Gere playfully snaps the lid of a jewelry case on Roberts’ fingers which was improvised by Gere, and Roberts’ surprised laugh was genuine. The necklace really cost $250,000 which resulted in a security man from the jewelry store equipped with a gun was constantly standing behind the director.

To produce the hysterical laughter during the scene where Vivian is lying down on the floor of Edward’s penthouse, watching re-runs of I Love Lucy, Marshall tickled Roberts’s feet (out of camera range) producing the genuine laughter shown in the film. During the famous scene in which Roberts sings along to Prince in the bathtub sliding down and dunking her head under the bubbles, Roberts came up and opened her eyes and saw that everyone had left the set, even the cameraman, who got the shot.

Roberts also had some difficulties during the love-making scene with Gere, getting so nervous that a vein visibly popped out on her forehead. She also developed a case of hives, and calamine lotion was given to clear them until shooting could resume. According to the DVD director’s commentary during the lovemaking scene on the piano, the piano key sounds that are made had to be dubbed in because the actual keys that were randomly hit by Julia and Richard as they did the scene. This resulted in such a discordant sound that it could not be used in the actual movie.

In its opening weekend, Pretty Woman opened at number one at the box office grossing $11,280,591 and remained number one at the box office for four non-consecutive weeks and in the top ten for sixteen weeks. It would go on to be the fourth highest-grossing film of 1990 in the United States and the third highest-grossing worldwide. Today it is still one of the most financially successful entries in the romantic comedy genre, with an estimated gross income of $463.4 million. The

film received mixed to positive reviews from critics, who particularly focused on the performance of Roberts. It received four Golden Globe Awards nominations: Best Motion Picture, Best Actor for Richard Gere, Best Supporting Actor for Hector Elizondo and won the Best Actress for Julia Roberts. Roberts would also earn her second Academy Award nomination and her first nomination for Best Actress for her work in the film.

Some Interesting Trivia:

Director Garry Marshall shares a fear of heights with Richard Gere’s character, Edward Lewis.

The original script was titled $3,000, but it was changed because executives at Touchstone thought it sounded like a title for a Science Fiction film.

Many of the unsavory traits given to the character of Vivian in the original script were removed or incorporated into the character of Vivian’s friend, Kit.

Some of the scenes filmed for the original darker version of the film were included on the DVD released on the film’s 15th anniversary such as a scene where Vivian is confronted by drug dealers outside The Blue Banana, and is rescued by Edward and Darryl.

For the film’s poster Julia Roberts’s head was superimposed on Shelley Michelle’s body and Richard Gere’s hair is brown on the poster but graying in the movie.

Julia Roberts earned $300,000 for her role.

Roberts prepared for her role by talking to prostitutes on Hollywood Boulevard.

The opera Richard Gere takes Julia Roberts to is La Traviata, which is about a prostitute who falls in love with a wealthy man.

Richard Gere is actually playing the piano. He also composed the piece of music that is played.

When Jason Alexander slams the door to his car they actually had to replace it, because the window broke.

The red coat that Vivian wears was bought for $30 from a movie usher in the street shortly before filming.

In the shots of the city in the very beginning, you will notice that some of the neon letters in the hotel where Vivian lives are burned out. The only remaining lighted letters spell “HO”.

Further Reading:

Pretty Woman: 15th anniversary. Buena Vista Home Entertainment, Touchstone. 2005.

Owen Gleiberman (1990-03-23). Pretty Woman. Entertainment Weekly.

A Christmas Story

Production Credits:

Director: Bob Clark | Producer: Bob Clark, René Dupont and Gary Goth | Screenplay: Jean Shepherd, Leigh Brown and Bob Clark | Cinematographer: Reginald H. Morris| Country of Origin: USA | Year: 1983 | Running Time: 93 min

Principal Cast: Peter Billingsley, Darren McGavin, Melinda Dillon, Jean Shepherd

While considered a Christmas classic today, at the time of its release 1983’s A Christmas Story received mostly negative reviews. Over the years, due in part to television airings and home video release, the film has become widely popular and is shown numerous times on television during the Christmas season. Today the film is celebrated for its nostalgic look at the 1940s and is considered a modern-day classic.

The film is based on a comic novel named In God We Trust, All Others Pay Cash, by radio humorist Jean Shepherd. Shepherd’s book is a collection of short stories that he wrote for Playboy magazine during the 1960s, including tales about fights with the bullies at school, and getting into impenetrable discussions with younger kids who do not quite know what all the words mean. He also includes stories about the tongue sticking to the flagpole, and eating Christmas dinner at a Chinese restaurant.

Due in part to the success of his teen raunch-fest Porky, director Bob Clark was given assignment of bringing Shepherd’s stories to the big screen. A Christmas Story was not Clark’s first time working in the holiday genre, as nine years earlier he had helmed the Yuletide slasher flick Black Christmas. According to Clark, he worked with writer Shepherd for nearly ten years on the concept of A Christmas Story before the film was made. The film was written by Shepherd, Clark and Leigh Brown. Shepherd also provides the movie’s narration from the perspective of an adult Ralphie.

For the film Clark assembled a wonderful cast of children, chief among them Peter Billingsley as protagonist Ralphie. Billingsley had first drawn notice as Messy Marvin in a series of commercials for Hershey’s Chocolate Syrup, and was considered a minor star after co-hosting the TV series Real People. While Clark had initially wanted him for the part of Ralphie, he had decided the he was “too obvious” a choice and auditioned many other young actors for the role. He would eventually realize that Billingsley was the right one after all and his performance in A Christmas Story is the one for which he will always be remembered. For the role of little brother Randy, Ian Petrella was cast immediately before filming began.

When it came to casting Ralphie’s father, Mr. Parker or “The Old Man”, the first actor director Clark had in mind was Jack Nicholson. Jack was very impressed with the script and was interested in doing the movie, but the studio didn’t want to pay Nicholson’s fee, which would have doubled the budget and went instead with Darren McGavin. Clark would later say that McGavin was the better choice as he was born to play the role. For the role of Mrs. Parker, Clark cast Melinda Dillon, (who was better known for her dramatic work) an Oscar nominated supporting actress for 1981’s Absence of Malice and 1977‘s Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

The film is set in Hammond Indiana (writer Shepherd’s hometown) and the search to find a current American city that resembled an Indiana town of the 1940s, had director Clark’s location scouts visiting over twenty cities. Cleveland Ohio was eventually chosen as the prinicipal site for filming, although parts of the movie, such as the Christmas tree shopping scene and Ralphie’s school exteriors, were filmed in Toronto and St. Catharines Ontario. (During the shot of the outside of the tree lot one of Toronto’s trademark red trolleys can be seen driving by.) Downtown Cleveland’s Higbee’s department store in was used for three scenes in the film including Ralphie and Randy’s visit to see Santa. The Santa slide used in the scene was made for the film but the store ended up using it for several years after the film’s release.

The people of Cleveland were incredibly cooperative during filming, donating antique vehicles from every corner of the city which helped to enhance the authenticity of the production design. During filming in downtown Cleveland, the antique automobile club members were given a route to follow on Public Square and were instructed to continue circling the square until otherwise instructed. Since road salt was a major concern for the car owners, the cars were pressure-washed after each day’s filming and parked underground beneath the Terminal Tower.

The Red Ryder BB Gun that Ralphie wants so desperately did exist at the time but it did not have a compass and sundial as mentioned in the movie. Apparently writer Shepard confused the Red Ryder gun with the Daisy “Buck Jones” model which did have those features. In order to support both the story and the screenplay, the compass and sundial were placed on Red Ryder BB guns specially made for the film. Interestingly the custom made guns placed the compass and sundial on the opposite side of the stock due to Peter Billingsley being left-handed.

A Christmas Story was released a week before Thanksgiving in 1983, and was considered a moderate success, earning about $2 million in its first weekend. Critics at the time were severely divided on the film, with the majority of reviews on the negative side. In fact by Christmas 1983, the film was no longer playing at most venues. During the mid-eighties HBO aired on television and it quickly attracted a growing following. In 1997 TNT began airing a 24-hour marathon dubbed “24 Hours of A Christmas Story,” consisting of the film shown twelve consecutive times beginning at 7 or 8 p.m. on Christmas Eve and ending Christmas Day.

Over the years, the film’s critical reputation has grown considerably and is considered by many to be one of the best films of 1983. A Christmas Story was on the ballot for the American Film Institute’s 100 Years… 100 Laughs list and both AOL and IGN ranked the film their #1 Christmas movie of all time.

Some Interesting Trivia:

For the scene in which Flick’s tongue sticks to the flagpole, a hidden suction tube was used to safely create the illusion that his tongue had frozen to the metal.

Director Bob Clark won the Genie Awards (the Canadian version of the Oscars) for Best Director and Best Screenplay.

Both Shepherd and Clark have cameo appearances in the film; Shepherd plays the man who directed Ralphie and Randy to the back of the Santa line and Clark plays Swede, the neighbor the Old Man was talking to outside during the Leg Lamp scene.

Ralphie says that he wanted the “Red Ryder BB Gun” 28 times.

According to Peter Billingsley, the nonsensical ramblings that Ralphie exclaims while beating up Scott Farkus were scripted, word for word.

An elaborate fantasy sequence – in which Ralphie joins Flash Gordon to fight Ming the Merciless – was filmed but dropped from the final cut.

The film inspired the creation of the television show The Wonder Years.

Today the St. Catharines Museum owns some props used in the film, including two pairs of Ralphie’s glasses (including the pair that were smashed) and two scripts.

For Further Reading:

Shepherd, Jean (1966). “My Old Man And The Lascivious Special Award That Heralded The Birth Of Pop Art” (Mass Market Paperback). In God We Trust All Others Pay Cash. Bantam Books.

Bob Clark and Peter Billingsley (2003). Audio Commentary: A Christmas Story (DVD special feature). MGM.

Shepherd, Jean (2003). A Christmas Story. New York: Broadway Books. indicia.

The Polar Express

Production Credits:

Director: Robert Zemeckis | Producer: Steve Starkey and Robert Zemeckis | Screenplay: Robert Zemeckis and William Broyles Jr. | Book: Chris Van Allsburg | Cinematographer: Don Burgess and Robert Pressley | Country of Origin: USA | Year: 2004 | Running Time: 100 min

Principal Cast: Tom Hanks, Michael Jeter, Nona Gaye, Peter Scolari, Steven Tyler

The Polar Express is a heartwarming story about the power of belief that resonates across generations and cultures. A young boy wanting to find out if Santa is real by hearing his sleigh bells finds instead a train on his lawn and embarks on an amazing adventure. The book is now widely considered to be a classic Christmas story for young children and has been praised for its detailed illustrations and calm, relaxing storyline. In 1986, its author, Chris Van Allsburg was awarded the Caldecott Medal for children’s literature. With its immense popularity, it was only a matter of time before the story made the move to film and in a way it is an appropriate fit as the author himself has said that when illustrating a book, he sees “the story unfold as if it were on film.”

The journey to turn the book into a film began with Tom Hanks, who approached Van Allsburg first about bringing The Polar Express to the big screen and then asked his friend Robert Zemeckis to adapt and direct the film version. Both Hanks and Zemeckis were determined that the film remain faithful to both the story and the feel of Van Allsburg’s book and realized that it couldn’t be a live-action movie in the traditional sense. For a solution, Zemeckis turned to visual effects master Ken Ralston who had worked at George Lucas’ Industrial Light and Magic. It was decided that the film version would take a cue from the lush illustrations in the book and use a new technology to – as Zemeckis explains – “give the visuals an elegance as if it were a moving oil painting.”

The result was the first feature length motion picture to be shot in “Performance Capture,” which is a motion capture process whereby the entire film is shot digitally with live actors and who are then replaced with computer generated doppelgangers. The actors, including Hanks (who voices five parts in the film, and was the live action model for “Hero Boy”), would wear Lycra suits covered with blue sensors that tracked their movements, which were then mapped to 3-D models in a computer so that the models would perform the same actions as the actors. In effect the film is live-action without any true “live” action. The process can be a challenge for the actors due to the lack of props and elaborate sets on which to base their performances, as they had to work in front of a green screen.

Other challenges that the filmmakers faced included expanding a 32-page picture book into a 100-minute feature-length film. This was done in two ways. Several scenes in the book were expanded, such as the “Hot Chocolate” production number, which was inspired by a single sentence and a single illustration in the original book. The introduction of new characters like the “Hobo,” the “Lonely Boy,” and the “Know-it-All” kid, and scenes such as those on rooftops and on the locomotive, and the runaway observation car sequence are also added to the film.

Filmmakers used actual places and machines in creating the world of The Polar Express including the steam locomotive that pulls the Polar Express which was modeled after the Pere Marquette No. 1225, a restored steam locomotive located in Owosso, MI. Artistic liberty was taken with the train’s appearance making it to seem even more massive than the 794,500 pound (361,136 kilogram) Pere Marquette but many of the train’s sound effects, such as the whistle blowing and steam exhausting, were created from live sampling of the actual train. Continuing the train theme, many of the buildings at the North Pole reference buildings related to American railroading history, such as the buildings in the square at the center of the city which were loosely based on the Pullman Factory located in Chicago, and the Control Center which was based on the old Penn Station in New York City.

The Polar Express was released in both standard theatrical 35mm format and in a 3-D version for IMAX, which was generated from the same 3-D digital models used for the standard version. It was the first animated feature not made specifically for IMAX to be presented in this format, and also the first to open in IMAX 3D at the same time as the general 35mm release. The response to the IMAX presentation was enthusiastic. The 3-D version out-performed the 2-D version by about 14 to 1. The film would go on to be nominated for three Academy Awards: Best Sound, Best Sound Editing, and Best Original Song. Today, for many, experiencing The Polar Express is an annual Christmas tradition, and a chance to remind us all that no matter your age, for those that truly believe, the bell will always ring.

Some Interesting Trivia:

The scene in the North Pole City communications room where an elf describes a bad little boy in New Jersey named Steven who is terrorizing his two little sisters is actually a nod to Zemeckis’ friend and mentor, Steven Spielberg. Spielberg grew up in New Jersey and has admitted many times that he frequently terrorized his two younger sisters.

The film would be actor Michael Jeter’s last movie before his death.

The real name of the Hero Boy is never mentioned.

The address spoken by the conductor early in the film “11344 Edbrooke” is the real address of Zemeckis’ childhood home.

For Further Reading:

Murray, Rebecca. Aug 25 2004. “Robert Zemeckis Directs Tom Hanks in ‘The Polar Express.’” About.com. http://movies.about.com/od/thepolarexpress/a/polar082504. htm

Roetenberg, D. 2006. “The Fascination For Motion – Introduction About The Beginning of Motion Capture Technology”. Inertial and Magnetic Sensing of Human Motion. PhD Thesis. http://www.xsens.com/en/company/research/human_mocap.php

Van Allsburg, Chris. 1986. The Polar Express 1986 Caldecott Medal Acceptance Speech. http://www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com/features/thepolarexpress/polarcaldecott.shtml

“The Polar Express.” TCM.com. http://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title.jsp?stid=452714

The Exorcist

Production Credits:

Director: William Friedkin| Producer: William Peter Blatty and Noel Marshall| Screenplay: William Peter Blatty | Cinematographer: Owen Roizman | Country of Origin: USA | Year: 1973 | Running Time: 122 minutes or 132 minutes (Director’s cut)

Principal Cast: Ellen Burstyn, Max von Sydow, Lee J. Cobb, Kitty Winn, Jack MacGowran, Jason Miller, Linda Blair

There have been very few films in the horror genre that have received as much attention or aroused such controversy among filmgoers as 1973’s The Exorcist. One of a cycle of ‘demonic child’ movies produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, (including Rosemary’s Baby and The Omen), this film is considered by many to be the best of the genre even though none of the cast or crew making it thought it would be so interesting, or affect audiences so much. Upon its release the film ignited a heated debate among the religious community, film critics, and audiences who were alternately repulsed and fascinated by its disturbing tale of good versus evil but today it is considered by many as one of the best and most effective horror films.

The film was based on the 1971 novel of the same name by William Peter Blatty, who adapted his work for the big screen . Prior to writing the novel Blatty won $10,000 on the Groucho Marx show You Bet Your Life and when Groucho asked what he planned to do with the money, he said he planned to take some time off to “work on a novel.” The Exorcist was the result. Blatty based his original novel on a strange incident which took place in Mt. Rainer, Maryland in 1949 involving a young boy named Ronald Hunkeler whose Catholic family, convinced the child’s aggressive behavior was due to demonic possession, called upon the services of Father Walter Halloran to perform the rite of exorcism. Blatty based other characters on real people, most notably the character of Chris MacNeil, whom he based on his good friend Shirley MacLaine. Coincidentally, MacLaine attempted to have a movie made of the novel (prior to the 1973 production), but the plans fell through.

Warner Brothers approached several prominent directors for the project including Arthur Penn (who was teaching at Yale), Peter Bogdanovich (who wanted to pursue other projects, but later regretted the decision), and Mike Nichols (who did not want to shoot a film so dependent on a child’s performance). Stanley Kubrick was interested in directing the film, but only if he could produce it himself and since the studio was worried that he would go over budget and over schedule, they finally hired Mark Rydell. Blatty was insistent on having William Friedkin direct instead, because he wanted his film to have the same energy as Friedkin’s previous one, The French Connection. A standoff between the author and the studio, who refused to budge over Rydell, began with Blatty eventually getting his way.

Both MacLaine and Jane Fonda were approached to play the role of Chris MacNeil as was Audrey Hepburn who only agreed to do it if it was filmed in Rome. Anne Bancroft was another choice for the part but since she was in her first month of pregnancy, she had to be dropped and the role went to Ellen Burstyn. The search for a young actress capable of playing Regan was apparently so difficult that Friedkin claims he even considered auditioning adult dwarf actors. Pamelyn Ferdin, a veteran of science fiction and supernatural drama, was a candidate but dismissed because the producers felt she was too well-known. Denise Nickerson (who played Violet Beauregarde in Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory) was also considered, but her parents pulled her out, troubled by the material. The agency representing Linda Blair overlooked her, recommending at least 30 other clients for the part of Regan and Blair’s mother had to bring her in herself to try out for the role.

For the role of Father Merrin the studio wanted Marlon Brando but Friedkin immediately vetoed this, stating that if Brando was in the film it would become a “Brando movie” instead of the important film he wanted to make. Both Jack Nicholson and Gene Hackman were considered for the part of Father Karras but it was given, at least initially, to Stacy Keach who was hired by Blatty. It was Friedkin who spotted Jason Miller in a Broadway play. Despite Miller never having acted in a movie before, Keach’s contract was bought out by Warner Brothers and Miller was cast in the role instead. Father Dyer was played by William O’Malley, an actual priest who still teaches to this day at Fordham University. Each year, O’Malley, who refers to the film as the “pornographic horror film” he once did, talks about his experience with the movie after students watch it on the same floor where it was filmed.

Production of The Exorcist began on August 14, 1972 and though it was only supposed to last 85 days, it lasted for 224. Interestingly, the last scenes of the movie to be filmed were the sequences in Iraq, which are the first you see in the movie. In order get permission to shoot in Iraq, Friedkin not only had to take an all-British crew (due to the fact that the US had no diplomatic relations with Iraq at that time) but also had to spend time teaching Iraqi filmmakers advanced film techniques as well as how to make fake blood. The MacNeil residence interiors were filmed at CECO Studios in Manhattan and an actual residence in Georgetown was used for the exterior shots. Set decorators were required to add a false wing to the residence in order to make Regan’s bedroom window closer to the infamous “Exorcist steps”. In reality, the window that led to Regan’s room was at least 40 feet from the top of the steps and at that distance it would be impossible for anyone “thrown” from the window to actually land on them. Other Georgetown locations used in the film included the steps of the Flemish Romanasque Healy Hall, Dahlgren Chapel, and the office of the president of the university (which was the Archbishop’s office in the film). The University was paid $1,000 per day of filming.

The bedroom set was refrigerated to capture the authentic icy breath of the actors in the exorcising scenes and Linda Blair, who was only in a flimsy nightgown, says to this day she cannot stand being cold. The refrigerated bedroom set was cooled with four air conditioners and temperatures would plunge to around 30 to 40 below zero. It was so cold that perspiration would freeze on some of the cast and crew and once the air was saturated with moisture that a thin layer of snow fell on the set before the crew arrived for filming.

Friedkin went to some extraordinary lengths, reminiscent of D.W. Griffith’s manipulation of his actors, to get realistic reactions from the cast. For example, in the scene when Father Dyer is attempting to administer last rites to Father Karris, Friedkin was not satisfied after several takes and took William O’Malley aside and asked, “Do you trust me?” O’Malley said yes just in time to get slapped across the face. Friedkin immediately said, “Action!” and the result is what one sees in the film. He would also fire off guns without warning behind the actors to get the required startled effect and even went so far as to put Linda Blair and Ellen Burstyn in harnesses and have crew members yank them violently. Both Blair and Burstyn suffered back injuries as a result; Blair was hurt when a piece of the rig broke as she was thrown about on the bed and Burstyn received a permanent spinal damage during the sequence where she is thrown away from her

possessed daughter. One scene that did not require any “help” from Friedkin to get the desired reaction was the scene where Regan projectile vomits on Father Karras. It only required one take. The vomit was supposed to hit him on the chest but the plastic tubing that sprayed the vomit accidentally misfired, hitting him in the face and the look of shock and disgust while wiping away the vomit was genuine. Actor Jason Miller, later admitted in an interview that he was very angered by this mistake.

Gonzalo Gavira was called on to create many of the special sound effects. One of the more memorable sounds, the 360-degree turning of Regan’s head, was created by taking an old, cracked leather wallet and twisting it back and forth against a microphone. Creating the effect of having the words “help me” arise out of Regan’s torso took several stages. First a foam latex replica of Blair’s belly was made, and then the words were written out using a paint brush and cleaning fluid. The words were then filmed as they formed from the chemical reaction. The forming blisters were then heated with a blow dryer by special effects artist Dick Smith, causing them to deflate. When the film was run backwards, the result was the appearance that the words were rising out of young Regan’s skin in an attempt to summon intervention.

In order to make Max von Sydow appear much older than his then age of 44, Smith first had to apply generous amounts of stipple to von Sydow’s forehead, eyes and neck. His facial skin was then manually stretched as liquid latex was applied and when the latex dried, his taut skin was then released causing the film of rubber to corrugate. The daily make-up procedure lasted three hours and was apparently the cause of much anguish for von Sydow. In a later interview Smith later reminisced about doing Blair’s make-up, saying:

The makeup involved approximately two hours or more every morning. We would start around 7 A.M. [Blair] was bored by the whole thing – you can’t blame her – so we had a little TV set sitting on a shelf on the opposite wall which she could see by looking in the mirror. It got to be a bit dodgy at times, because if I would get in the way of the reflection of the TV set, she would move her head in order to continue seeing what The Flying Nun [the TV series starring Sally Field] was up to, and it just made it difficult to do the makeup.

On the first day of filming the infamous exorcism sequence, Blair’s delivery of her foul-mouthed dialogue so disturbed the gentlemanly Max von Sydow that he actually forgot his lines. For any of the demon’s dialogue, Friedkin had originally intended to electronically deepen and roughen Blair’s own voice but although it worked in some places, he felt the scenes when the demon confronts the two priests lacked the dramatic power required. He thus selected legendary radio actress Mercedes McCambridge, (an experienced voice actor) to provide the demon’s voice. To get the desired effect for the demon Pazuzu’s voice, McCambridge went through bouts of chain smoking and vomiting. When the film was released, Warner Brothers attempted to conceal McCambridge’s participation which led to a lawsuit from the actress and a grudge

between her and Friedkin that was never healed.

One of the most recognized scenes from the film was not actually in original release. The infamous spider-walk scene, which was performed by contortionist Linda R. Hager on April 11, 1973, was deleted just prior to the original December 26, 1973 premiere because Friedkin felt it was technically ineffective due to the visible wires suspending Hager in a backward-arched position as she descends the stairs (he also felt that the scene appeared too early in the film’s plot). According to Friedkin, “I cut it when the film was first released because this was one of those effects that did not work as well as others, and I was only able to save it for the re-release with the help of computer graphic imagery.” Years later, to appease the fans of the film, Friedkin worked with CGI artists to digitally remove the wires holding Hager and reinstated the bloody variant of the spider-walk scene for the 2000 theatrically re-released version of The Exorcist: The Version You’ve Never Seen.

Many of the film’s participants claimed the film was cursed. Blatty stated on video that there were some strange occurrences during the filming and Burstyn indicated some rumors were true in her 2006 autobiography Lessons in Becoming Myself. A studio fire caused the interior sets of the MacNeil residence (with the exception of Regan’s bedroom) to have to be rebuilt and resulted in a setback in pre-production. Friedkin eventually asked technical advisor Thomas Bermingham to exorcise the set. After his refusal, Rev. Bermingham, during a visit to the set, gave a blessing and talk to reassure the cast and crew. In order to bring some levity to the shoot, Blatty suggested shooting a scene (not for the movie, but to amuse everyone at the screening of the rushes) in which Father Merrin would enter the house, take off his hat, and reveal himself to be Groucho Marx, who was a friend of Blatty’s. Groucho was keen to do it, but Friedkin was sick the day it was planned and so the idea was abandoned.

The original teaser trailer for the film, which consisted of nothing but images of the white-faced demon quickly flashing in and out of darkness, was banned in many theaters, as it was deemed “too frightening”. The reaction continued during the film’s initial theatrical release. Many audiences reacted so strongly that at many theaters, paramedics were called to treat people who fainted and others who went into hysterics. A filmgoer who saw the movie in 1974 fainted and broke his jaw on the seat in front of him. He then sued Warner Brothers and the filmmakers, claiming that the use of subliminal imagery in the film had caused him to pass out. The studio settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. Blatty later mused that it wasn’t the supernatural/demonic sequences that caused, nausea in the aisles and inspired patrons to flee theater but instead it was the scene in which Regan undergoes carotid angiography, using direct carotid puncture and pneumoencephalography which upset theatergoers.

When originally released in the UK a number of town councils imposed a complete ban on the showing of the film. This led to the bizarre spectacle of “Exorcist Bus Trips” where enterprising travel companies organised buses to take groups to the nearest town where the film was showing. The film was not available on video in the UK until 1999 when the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) approved an uncut version.

The Exorcist went on to earn ten Academy Award nominations and won two: Best Sound and Best Adapted Screenplay. It would also be the first horror film to ever be nominated for Best Picture Academy Award, losing it to The Sting. Blair received her Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination before it was widely known that previous Supporting Actress winner Mercedes McCambridge had actually provided the voice of the demon. By Academy rules once Blair was given the nomination it could not be withdrawn, but the controversy surrounding Blair being given credit for another actress’ work are thought to have ruined her chances of winning.

The Exorcist earned $66.3 million during its theatrical release in 1974, becoming the second most popular film of that year (after The Sting).After several reissues, the film eventually grossed $232,671,011 in the North America, which if adjusted for inflation, would make it one of the top-grossing R-rated films of all time. The film has had a huge effect on popular culture and has been named the scariest movie of all time by Entertainment Weekly, Maxim and by viewers of AMC in 2006. In 2010 the film was selected to be preserved by the Library of Congress as part of its National Film Registry of culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant films.

Some Interesting Trivia:

Due to death threats against Linda Blair from religious zealots who believed the film “glorified Satan”, Warner Bros. had bodyguards protecting her for six months after the film’s release.

The entire exorcism scene, from start to end, lasts 9 minutes. Three separate beds were built to do three separate movements.

According to Variety magazine, Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds both were contenders for the roles of Regan and Chris MacNeil.

The substance that the possessed Regan (Linda Blair) hurls at Father Damien Karras (Jason Miller) is thick pea soup. Specifically, it’s Andersen’s brand pea soup. The crew tried Campbell’s but didn’t like the “effect.”

The nurse who comes into Dr. Taney’s office after the arteriogram is actress Linda Blair’s mother, Elinore Blair.

The subliminal shots of the white faced demon are actually rejected makeup tests for Regan’s possessed appearance.

The archaeological dig site seen at the beginning of the movie is the actual site of ancient Nineveh in Hatra, Iraq.

The “Exorcist steps” are 75 (or 74 – one is very small) stone steps at the end of M Street in Georgetown, which were padded with 1/2″-thick rubber to film the death of Father Karras. The stuntman tumbled down the stairs twice and Georgetown University students charged people around $5 each to watch the stunt from the rooftops.

Author William Peter Blatty was barred from all post-production work by Friedkin after a major dispute.

Christian evangelist Billy Graham claimed an actual demon was living in the celluloid reels of this movie.

For Further Reading:

Travers, Peter and Rieff, Stephanie. The Story Behind ‘The Exorcist’, Signet Books, 1974.

The Shining

Production Credits:

Director: Stanley Kubrick| Producer: Stanley Kubrick, Jan Harlan and Martin Richards | Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick and Diane Johnson| Cinematographer: y John Alcott| Country of Origin: USA| Year: 1980 | Running Time: 144 minutes (US cut), 119 minutes (International cut), 146 minutes (Original cut)

Principal Cast: Jack Nicholson, Shelley Duvall, Danny Lloyd, Scatman Crothers

Although The Shining is now regarded by many as a horror classic, back at the time of its original 1980 theatrical release, it was considered something of a bust. However, much like how the ghostly apparitions of the film’s Overlook Hotel

would play tricks on the mind of poor Jack Torrance, so too has the passage of time changed the perception of the film itself. The same reviewers who criticized the film in 1980 for “not being scary” enough, now rank it among the most

effective horror films ever made, while audiences who hated the film back then now vividly recall being “terrified” by the experience. The Shining has somehow redefined itself not only as an influential member of the horror genre, but perhaps

the most artful horror film ever made.

Director Stanley Kubrick first approached author Stephen King about making a film version of his 1977 novel The Shining in an early morning phone call. King later recalled how shocked he was when his wife told him who was really on the

phone and remembered that the first thing Kubrick did in their conversation was to start talking about how optimistic ghost stories are, because they suggest that humans survive death.

For his film adaptation, Kubrick rejected a screenplay written by King himself. King’s script was a much more literal adaptation of the novel, creating a much more traditional horror film. Kubrick would end up hiring as his writing partner

novelist Diane Johnson. Several changes were made from the book, such as using a hedge maze for the film’s climax, instead of having the hedge animals come alive (as they do in the book) which was considered impractical due to

restrictions in special effects. Changes to the script were made constantly during filming, to the point that star Jack Nicholson claimed he stopped reading it and would read only the new pages that were given to him each day.

For the lead role of Jack Torrance, Kubrick considered both Robert De Niro and Robin Williams but decided against both of them; Kubrick felt that De Niro was not psychotic enough for the part after watching his performance in Taxi Driver,

whereas he deemed Williams too psychotic after watching his performance in Mork & Mindy. According to Stephen King, Harrison Ford was also briefly considered. King tried to talk Kubrick out of casting Jack Nicholson in the lead

and suggested either Michael Moriarty or Jon Voight instead; King felt that watching either of these normal looking men gradually descend into madness, would have immensely improved the dramatic thrust of the storyline.

Much like the casting of Jack Torrence, King also disliked the casting of Shelley Duvall as Wendy Torrence. King felt that Duvall was too emotionally vulnerable and appeared to have gone through a lot in her life, which was basically the exact

opposite of what he had envisioned Wendy as being; King saw her as a blond former cheerleader type who never had to deal with any true problems in her life which made her experience in the Overlook all the more terrifying. Nicholson,

after reading the novel, wanted Jessica Lange for the part of Wendy, and even recommended her to Kubrick, as he felt she fit King’s version of the character. However Kubrick had envisioned Duvall as his more timid, dependent version of Wendy from the very beginning and after explaining the changes he had made, Kubrick convinced Nicholson that Duvall was the correct choice. Many years later, Nicholson told EMPIRE magazine that he thought Duvall was fantastic and

called her work in the film, “the toughest job [of] any actor that I’ve seen.”

Kubrick’s first choice to play the role of Danny Torrance was Cary Guffey (the young boy from Close Encounters of the Third Kind) but Guffey’s parents turned down the offer, apparently due to the film’s subject matter. Open auditions were

held over a six month period in Chicago, Denver and Cincinnati by Kubrick’s assistant Leon Vitali and his wife, Kersti. Aspiring actors were asked to send in photographs of themselves, and from those, a list was made of the boys who

looked right, who were then called in to do some minor improvisation on camera. Kubrick would review the footage and narrow the list down. The part would eventually go to 6 year old Danny Lloyd. Since Lloyd was so young and because it

was his first acting job, Kubrick was highly protective of him. During the shooting of the movie, Lloyd was under the impression that he was making was a drama, not a horror movie and only realized the truth seven years later, when he was shown a heavily edited version of the film. It wasn’t until he was 17 (eleven years after he’d made it) that he saw the uncut version of the film.

The Timberline Lodge on Mt. Hood in Oregon was used for the exterior of the Overlook Hotel, but all of the interior rooms of the hotel were filmed at Elstree Studios in England, including The Colorado Lounge, where Jack does his typing. To construct the interiors of the Overlook, Kubrick and his production designer, Roy Walker purposely set out to make it look like an amalgamation of bits and pieces of real hotels, rather than giving it one single design ethic. The hedge maze was constructed on an airfield near Elstree studios, by weaving branches to chicken wire mounted on empty plywood boxes. The scenes in the maze were shot using an extremely long lens (a 9.8mm, which gives a horizontal

viewing angle of 90 degrees) which was kept dead level at all times in order to make the hedges seem much bigger and more imposing than they were in reality. The “snowy” maze near the conclusion of the movie consisted of 900 tons of salt

and crushed Styrofoam.

Cast and crew found shooting difficult at times due to the lack of air conditioning which caused the sets to become overly hot. The hedge maze set for example was so stifling that actors and crew would often strip off as much of the heavy

clothing they were wearing as quickly as possible once a shot was finished. The intense heat generated from the lighting used to recreate window sunlight (the room took 700,000 watts of light per window to make it look like a snowy

day outside) caused a fire on the set of the Colorado Lounge. Fortunately all of the scenes using that set had been completed, so there was no further delay to shooting. It was simply rebuilt with a higher ceiling. The same set was eventually used by Steven Spielberg as the snake-filled Well of the Souls tomb in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The Shining had a prolonged and arduous production period, often with very long workdays, which was due in large part to Kubrick’s highly methodical nature and trademark style of repetitive takes. While Variety magazine reported that

the film took almost 200 days to shoot, according to assistant editor Gordon Stainforth, it took nearly a year. Because filming ran so long, other productions who were waiting to shoot in Elstree Studios were delayed, including both

Warren Beatty’s Reds and Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. Part of the delay was the result of Kubrick wanting to shoot the film in script order which required all the relevant sets standing by at all times; in order to achieve this,

every soundstage at Elstree was used, with all the sets built, pre-lit and ready to go during the entire shoot.

Despite Kubrick’s fierce demands on everyone, Nicholson later admitted to having a good working relationship with him. For Duvall however he was a completely different director, allegedly picking on her more than anyone else (as

seen in the documentaries Making ‘The Shining’ and Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures). He would really lose his temper with her, even going so far as to say that she was wasting the time of everyone on the set. On the DVD commentary

track for Making ‘The Shining’, Vivian Kubrick reveals her father’s tactic to make Duvall feel utterly hopeless, was ensure she received “no sympathy at all” from anyone on the set; this is most evident in the documentary when Kubrick

tells Vivian, “Don’t sympathize with Shelley” and then goes on to tell Duvall, “It doesn’t help you.” Duvall later reflected that Kubrick was probably pushing her to her limits to get the best out of her, and she wouldn’t trade the experience for

anything, but it was not something she ever wished to repeat.

Kubrick, despite his usual compulsiveness and numerous retakes, was able to get the difficult shot of blood pouring from the elevators in only three takes which would be remarkable if it weren’t for the fact that the shot took nine days to set

up; every time the doors opened and the blood poured out, Kubrick would say, “It doesn’t look like blood.” In the end, the shot took approximately a year to get right. For the any of the scenes when the audience can hear Jack typing but cannot see it, Kubrick recorded the sound of a typist actually typing the words “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”. Kubrick wanted to ensure authenticity, and since some people argue that each key on a typewriter sounds slightly different, he insisted that the actual words be typed.

One filming technique used in the principal photography of The Shining was the then revolutionary Steadicam technique; it was Kubrick’s first picture to use it and it was actually among the first half dozen films to incorporate it. Many of the

ultra-low tracking corridor sequences were accomplished by Steadicam inventor/operator Garrett Brown from a wheelchair on which his invention was mounted. Grips would either pull backward or push forward the wheelchair, depending on the requirement of the shot. Brown was hired to work on the picture with the assurance that there was no way the shoot would run over six months (Brown had to be back in the US in six months time to shoot Rocky II) however six months into the shoot, less than half the film had been shot. For the next several months, Brown would work one week in London on The Shining, and one week in Philadelphia on Rocky commuting by Concorde every Sunday.

The scene in the film where Jack is throwing around a tennis ball inside the hotel instead of writing was actually Nicholson’s idea; the scene as originally scripted only specified that, “Jack is not working”. To get the shot of the ball bouncing from the wall onto the camera lens as it filmed, actually took several days to film. Kubrick was so determined to get this precise shot, the camera kept rolling while the ball was continually hit against the wall in the hope of it bouncing back and hitting the lens. It took everyone on the entire unit having a go at it in between other shots before the shot was finally achieved.

For the iconic scene in which Jack breaks down the bathroom door, the props department built a door that could be easily broken. However, Nicholson had worked as a volunteer fire marshal and tore it apart far too easily which

forced the props department to build a stronger door. According to Duvall the scene took 3 days to film and used 60 doors. Interestingly, the scene’s infamous “Heere’s Johnny!” line was never in the original script. Nicholson ad-libbed the line during filming in an imitation of announcer Ed McMahon’s famous introduction of Johnny Carson on NBC’s long-running late night television program The Tonight Show. Kubrick, who had been living in England since before Carson took over The Tonight Show, had no clue what “Heere’s Johnny!” meant but decided to keep that take anyway. Carson would later use the clip of Nicholson as the introduction to one of his annual anniversary specials.

After its premiere and a week into the general run (with a running time of 146 minutes), Kubrick cut about 2 minutes from the end of the film. The excised scene shows Wendy in a hospital bed talking with Mr. Ullman who explains that Jack’s body could not be found; he then gives Danny a yellow tennis ball, presumably the same one that lured Danny into Room 237. After meeting with poor reviews and erratic box office, Kubrick decided to further edit the film for its theatrical release outside the US. He cut approximately 31 minutes of footage, reducing the length to 113 minutes.

When the film was released, Stephen King was quoted as saying that although Kubrick made a film with memorable imagery, it was not a good adaptation of his novel and is in fact the only adaptation of his novels that he could “remember

hating”; His dissatisfaction with the film would lead King to produce his own version of The Shining as a mini-series for television in 1997. However, King’s animosity toward Kubrick’s adaptation appears to have dulled over time. During

an interview segment on the Bravo channel, King admitted that the first time he watched Kubrick’s adaptation, he found it to be “dreadfully unsettling.”

Despite receiving generally unfavorable reviews upon its initial release, The Shining is today regarded as one of the best horror movies ever made. The film was voted the ninth scariest film of all time by Entertainment Weekly and in

2001, it was ranked 29th on AFI’s ‘100 Years…100 Thrills’ list. In 2003, Jack Torrance was named the 25th greatest villain on the AFI’s ‘100 Years…100 Heroes and Villains’ list.

Some Interesting Trivia:

During the making of the movie, Stanley Kubrick would occasionally call Stephen King at 3:00 a.m. and ask him questions like “Do you believe in God?”

The idea for Danny Lloyd to move his finger when he was talking as Tony was his own; he did it spontaneously during his very first audition.

The management of the Timberline requested that Kubrick not use 217 for a room number (as specified in the book), fearing that nobody would want to stay in that room ever again. Kubrick changed the script to use the nonexistent room number 237.

During the scene where Wendy brings Jack breakfast in bed, it can be seen in the reflection of the mirror that Jack’s T-shirt says “Stovington” on it. While not mentioned in the film, this is the name of the school where Jack taught at in the novel.

The scene towards the end of the film, where Wendy is running up the stairway carrying a knife, was shot 35 times; the equivalent of running up the Empire State Building.

During an interview for the UK’S The 100 Greatest Scary Moments, Duvall revealed that because her role required her to be in an almost constant state of hysteria, she eventually ran out of tears from crying so hard and had to keep bottles of water with her at all times on set to remain hydrated.

The 144 minute ‘US version’ is often erroneously called the Director’s Cut when in fact director Kubrick regarded the 113 minute version as the superior cut of the film.

Outtakes of the shots of the Volkswagen traveling towards the Overlook at the start of the film were plundered by Ridley Scott (with Kubrick’s permission) when he was forced to add the ‘happy ending’ to the original release of Blade Runner.

Tony Burton, who had a brief role as Larry Durkin the garage owner, arrived on set one day with a chess set in hopes of getting in a game with someone during a break from filming. Kubrick, an avid chess player who had in his youth played for money, noticed the chess set and despite production being behind schedule, proceeded to call off filming for the day and engage in a set of games with Burton. Burton only managed to win one game, but nevertheless the director thanked him, saying it had been some time that he’d played against a challenging opponent.

The book that Jack was writing contained the one sentence (“All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”) repeated over and over. Kubrick had each page individually typed. For the Italian version of the film, Kubrick used the phrase “Il mattino ha l’ oro in bocca” (“He who wakes up early meets a golden day”). For the German version, it was “Was Du heute kannst besorgen, das verschiebe nicht auf Morgen” (“Never put off till tomorrow what you can do today”). For the Spanish version, it was “No por mucho madrugar amanece más temprano” (“Rising early will not make dawn sooner.”). For the French version, it was “Un ‘Tiens’ vaut mieux que deux ‘Tu l’auras'” (“A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush”).

For Further Reading/Viewing:

Vivian Kubrick’s Making ‘The Shining’ (1980)

Jan Harlan’s Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures (2001)

Diane Johnson’s essay “Writing The Shining” in anthology “Depth of Field” by Cocks, Diedrick, and Perusek,

LoBrutto, Vincent. Stanley Kubrick: A Biography,

Browning, Mark. Stephen King on the big screen

Scorsese, Martin (October 28, 2009). “11 Scariest Horror Movies of All Time”. The Daily Beast.

The Silence of the Lambs

Production Credits:

Director: Jonathan Demme | Producer: Kenneth Utt, Edward Saxon and Ron Bozman| Screenplay: Ted Tally | Cinematographer: Tak Fujimoto | Country of Origin: USA | Year: 1991 | Running Time: 118 min

Principal Cast: Jodie Foster, Anthony Hopkins, Scott Glenn, Ted Levine

It’s by no mistake that The Silence of the Lambs is still considered one of the most taut, suspenseful, psychological thrillers of all time. The reason, simply, is that no other film looks or feels like it, and even though its influence is still strong today, there has still never been a strong successor to it.

The film is based on 1988’s best-selling novel of the same name by former crime and police reporter Thomas Harris, who was inspired by the real life relationship between criminology professor and profiler Robert Keppel and serial killer Ted Bundy; while incarcerated Bundy helped Keppel in his investigation of the Green River Serial Killings in Washington. Harris would also base several characters on real people such as Buffalo Bill (aka Jame Gumb) who was the combination of three real-life serial killers: Ted Bundy, who used the cast on his hand as bait to make women get into his van, Gary Heidnick, who kept women he kidnapped in a pit in his basement and Ed Gein, who skinned his victims. (Gein would also inspire the character of Psycho’s Norman Bates). The character of Jack Crawford was based on real-life FBI Special Agent John E. Douglas, an early member of the FBI’s Behavioral Sciences Unit.

The rights to The Silence of the Lambs were originally bought by Gene Hackman, (who was planning to both direct and star in the film), but he later withdrew from the project. When producers looked to cast the role of the imprisoned psychopath, Dr. Hannibal Lecter, it is rumored they considered several well-known actors including Christopher Lloyd, Patrick Stewart, Louis Gossett Jr., Robert Duvall, Jack Nicholson, and Robert De Niro. Director Jonathan Demme’s first choice for the role was Sean Connery, but he turned the part down, as did second choice Jeremy Irons. British actor Anthony Hopkins was finally cast as Lecter, based in part on his performance as the kind-hearted Dr. Frederick Treves in 1980’s The Elephant Man. When Hopkins found this out he questioned director Demme, saying “But Dr. Treves was a good man.” To which Demme replied “So is Lecter, he is a good man too. Just trapped in an insane mind.”

According to Demme, there were 300 applicants for the role of Clarice Starling, including Geena Davis, Melanie Griffith, and Meg Ryan. While writing the screenplay for the film screenwriter Ted Tally suggested Jodie Foster for role. Foster had already been lobbying hard for the part (after she had read the novel, Foster tried to buy the rights herself, only to find Gene Hackman had beaten her to it) but when Demme was hired to direct the film, he felt she was wrong for the role and wanted Michelle Pfeiffer instead. Pfeiffer turned it down, saying later, “(It was) a difficult decision, but I got nervous about the subject matter”. Demme then agreed to meet Foster and hired her after only one meeting because he said he could see her strength and determination which he felt was perfect for the character of Clarice.

The real-life FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit assisted in the making of this film. Foster, Demme and Scott Glenn, and a few other cast and crew members, did a great deal of research at the FBI training facility in Quantico, Virginia where they studied under criminal profiling agents, learned about firearms and agent training, and sat in on a number of classes. Foster spent a great deal of time with agent Mary Ann Krause and it was Krause who gave Foster the idea of Starling standing by her car crying (As Krause told Foster, at times the work just became so overbearing that this was a good way to get an emotional release). Agent John E. Douglas coached Scott Glenn on his portrayal of a member of the BSU. Douglas was still an active FBI Special Agent during production, and was in the midst of tracking Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer.

In preparation for their roles, both Hopkins and Ted Levine studied files of serial killers (Levine later said that he found the material very disturbing). Hopkins also visited prisons, studied convicted murderers and was present during some court hearings concerning serial killings while Levine went out and attended a few transvestite bars, where he began interviewing patrons, since Bill was also a cross-dresser.

Principal photography began November 15, 1989, lasting just over 3 months. Much of the shoot took place in the city of Pittsburgh, PA. It was chosen for its variety of landscapes and architecture, which was necessary to portray various parts of the country. Some of the most memorable scenes, including the Baltimore jail scene and the ballroom scene of Lecter in his cage, were shot in Soldiers and Sailors Memorial located on Fifth Avenue in the Oakland area of Pittsburgh.

The filmmakers had completely prepared to go to Montana to shoot a flashback sequence depicting Clarice’s runaway attempt, but after filming the dialogue between Foster and Hopkins, Demme realized it would be pointless to cut away from their performances and announced, “I guess we aren’t going to Montana.”

Several key changes were made from the original script such as the film was originally to open with Clarice Starling and a male FBI agent bursting into a room, making a number of arrests, and only then would the audience be let in on the fact that it was a training exercise. Foster convinced director Demme to change this scene, as she felt it had been done so many times before and it was Foster herself who came up with the idea of opening with Starling running through the assault course. In an early version of Tally’s screenplay, Lecter’s ingenious and horrific ruse to escape from captivity in the courthouse is given away by the head of SWAT team (when the top half of the body on the top of the elevator swings down), recognizing the body. In the final version the film cuts straight to the ambulance and Lecter’s unmasking.

The end of the film was also changed from Harris’ book which concludes with Lecter writing a threatening letter to Dr. Chilton. Both Tally and Demme decided that having Lecter track Chilton to a tropical island would provide a more dramatic and audience-pleasing closing (in addition to an all-expense studio-paid trip to shoot somewhere warm).

Some of Lecter’s iconic character elements were suggested by Hopkins himself such as how Lecter look directly at the camera as it panned into his line of sight during the scene where Lecter and Starling first meet. Hopkins felt Lecter should be portrayed as “knowing everything.” Hopkins was also able to convince Demme and costume designer Colleen Atwood that if they dressed Lecter in pure white, it would make the character seem more clinical and unsettling, in the scene after Lecter was moved from Baltimore (Hopkins has since said that this idea came from his fear of dentists); Lecter was originally to be dressed in a yellow or orange jumpsuit.

The fast, slurping-type sound that Lecter does was invented by Hopkins spontaneously during filming, and everyone thought it was great. Apparently Demme became annoyed with it after a while, but always denied his irritation. Foster claims that while filming the first meeting between Lecter and Starling, Hopkin’s mocking of her southern accent was not rehearsed and improvised on the spot. She felt personally attacked and so her reaction of horror was totally genuine (though she later thanked Hopkins for generating such an honest reaction).

The film sparked controversy within the gay community for its’ portrayal of the serial killer Buffalo Bill as a wannabe transsexual with stereotypical gay mannerisms. Gay rights protesters attended film screenings, complaining that making Buffalo Bill a transsexual was highly clichéd and pandered to public hostilities around the issue of sexual orientation diversity.

It has long been rumored that the novel’s author Thomas Harris had never watched the film because he was afraid it would influence his writing. According to a New York Magazine profile of Harris, Harris saw the film shortly after it came out and said

“It’s a great movie … I’ve been surrounded by it, so I wanted to see it. I admire Jonathan Demme, and we were very fortunate to have him and screenwriter Ted Tally, and we were very lucky with the cast.”‘

When The Silence of the Lambs was released on February 14, 1991, it received much critical acclaim with Hopkins, Foster and Levine especially being praised for their performances. The film won the top five Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Actor, Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay (a feat that has only happened twice before for It Happened One Night and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest). The Silence of the Lambs placed seventh on Bravo’s 100 Scariest Movie Moments for Lecter’s infamous escape scene and the American Film Institute named Hannibal Lecter (as portrayed by Hopkins) the number one film villain of all time.

Some Interesting Trivia:

Anthony Hopkins is only onscreen for little more than 16 minutes.

Hopkins described his voice for Hannibal Lecter as, “a combination of Truman Capote and Katharine Hepburn.”

The character of Hannibal “the Cannibal” Lecter was born as a secondary character in the Thomas Harris’ 1981 novel Red Dragon.

Brooke Smith who played Catherine Martin and Ted Levine who played Buffalo Bill were actually very close on the set, making Jodie Foster refer to Brooke Smith as Patricia Hearst (meaning a woman that is actually close with her kidnapper).

Buffalo Bill’s dance was not included in the original draft of the screenplay (although it appears in the novel). It was added later at the insistence of Levine, who felt the scene was essential in defining the character.

Like Casablanca, this movie contains a famous misquoted line: most people quote Lecter’s famous “Good evening, Clarice” as “Hello, Clarice.”

In his first meeting with Clarice Starling, Lecter describes the drawing on his cell wall as “the Duomo, seen from the Belvedere” in Florence, Italy. Lecter’s line, which in fact foreshadows Buffalo Bill’s location as Starling later finds him living in Belvedere, Ohio.

Almost all the scenes in Hannibal’s original cell have either a reflection of Hannibal or Clarice, depending on the camera’s point of view.

The first moth cocoon found in one of the victim’s throats was made from a combination of “Tootsie-Rolls” and gummy bears, so that if she swallowed it, it would be edible.

Then Secretary of Labor, Elizabeth Dole’s, Washington, D.C. office doubled for that of the F.B.I. director’s office in the movie.

This was the first film to win the Best Picture Oscar that was widely available on home video at the time of the ceremony.

The Silence of the Lambs was the last hit released by Orion Pictures before the company went bankrupt the following year.

For Further Reading:

Kapsis, Robert, E., ed. Jonathan Demme: Interviews (Conversations with Filmmakers Series). Jackson, Mississippi: University of Mississippi, 2009

Hoban, Phoebe (15 April 1991),”The Silence of the Writer,” New York Magazine

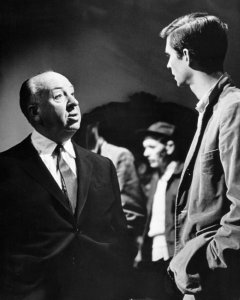

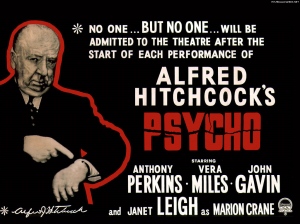

Psycho

Director: Alfred Hitchcock | Producer: Alfred Hitchcock | Screenplay: Joseph Stefano | Cinematographer: John L. Russell | Country of Origin: USA | Year: 1960 Running Time: 109 min.

Principal Cast: Anthony Perkins, Vera Miles, John Gavin, Martin Balsam, John McIntire, Simon Oakland, Janet Leigh

One of the most talked about movies of its day was Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), and nearly fifty years later, film lovers still discuss it. While initially receiving mixed reviews, it is now considered one of Hitchcock’s best films and is highly praised as a work of cinematic art. The film is based on the 1959 novel of the same name by Robert Bloch. which is based loosely on the case of convicted Wisconsin murderer Ed Gein. Like Gein, Bloch’s protagonist Norman Bates, is a solitary murderer in an isolated rural location, has a deceased domineering mother, and has sealed off one room in his house as a shrine to his mother.

The book was brought to director Alfred Hitchcock’s attention by his production assistant Peggy Robertson, who had read a positive review of the Bloch novel. Hitchcock would later say “I think the thing that appealed to me [about the book] and made me decide to do the picture was the suddenness of the murder in the shower, coming, as it were, out of the blue,” The director had also wanted to make a radical departure from the big budget widescreen color thrillers he had recently turned out, such as Vertigo (1958) and North by Northwest (1959), and felt that Bloch’s novel was the ideal subject matter. He bid on the rights anonymously, (assuming more money would have been demanded if it was known Hitchcock was interested), and got them for $9,000. It was only after the deal was finalized that Bloch learned the identity of the his mystery buyer.

His bosses at Paramount were stunned when Hitchcock decided his next project would be Psycho. They were expecting him to complete No Bail for the Judge starring Audrey Hepburn, which had been scrapped when the actress became pregnant and had to bow out. Paramount did not want to produce the film and flatly refused finance it, telling him their sound stages were occupied or booked even though production was known to be in a slump. Realizing that the studio expected the film to fail miserably at the box office, Hitchcock countered with the offer to finance the film personally through his own Shamley Productions and to film it at Universal if only Paramount would distribute it. He also deferred his usual director’s fee of $250,000 for a 60% ownership of the film negative (he ended up making millions of dollars from his gamble due to the films success); this offer was finally accepted.

To keep costs down and because he was most comfortable around them, Hitchcock used most of his crew from his television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, such as the cinematographer, set designer, and script supervisor. He hired Bernard Herrmann as music composer, and George Tomasini as editor, both of whom were regular collaborators. In all, his crew cost $62,000. Even the sets were relatively cheap, with the sinister Bates house costing a mere $15,000 to build (the steeple was actually salvaged from a house used in 1950‘s Harvey)

James Cavanaugh, who had written for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, wrote the original screenplay but Hitchcock rejected it, saying that the story dragged and read like a television short horror story. To replace him, Hitchcock reluctantly agreed to meet with writer Joseph Stefano, who had worked on only one film before. Stefano later said that he won Hitchcock’s approval by making the first forty five minutes of the film about Marion and beginning the screenplay with the scene between Marion and Sam (the book begins with a conversation between Norman and his mother). While the final screenplay is relatively faithful to the novel, there are a few notable adaptations such as the character of Norman Bates. In the book, he is middle aged and more overtly unstable and unsympathetic. Stefano eliminated Bates’ drinking, changed why Bates’ “became” Mother (in the novel he does so in a drunken stupor). The novel is more violent than the film; for instance, Crane is beheaded in the shower, as opposed to being stabbed to death. Minor alterations included changing the location of Arbogast’s death which was moved from the foyer to the stairwell, changing the name of the female protagonist from Mary Crane to Marion Crane, and the down playing of the novel’s budding romance between Sam and Lila as Hitchcock preferred to focus the audience’s attention on the solution to the mystery.

Stefano and Hitchcock deliberately layered in certain risqué elements as a ruse to divert the censors from more crucial concerns like the action that takes place in the bedroom in the beginning and the shower murder. The censors reviewed the script and censored the “unimportant” extra material and Hitchcock managed to sneak in his “important” material.

Because he was working with a low budget, Hitchcock did not want to use top marquee names with the exception of Janet Leigh and he hired her because he knew audiences would be shocked to see a star of her stature killed off early in the movie. Modern sources indicate that Eva Marie Saint, Piper Laurie, Hope Lange, Shirley Jones and Lana Turner were also considered for the role of Marion. Despite only wanting to use one well known star in the film, the rest of the cast were hardly unknowns. Anthony Perkins was a fast rising young actor with a number of important pictures to his credit prior to Psycho including Friendly Persuasion [1956]. He was paid $40,000 for his work, almost twice what Janet Leigh received and coincidentally the same sum that Marion Crane steals in the story. While the success of Psycho jump-started Perkins’s career, he would soon began to suffer from typecasting. When asked later whether he would have still taken the role knowing that he would be typecast afterward, Perkins replied with a definite “yes.”

One major issue Hitchcock faced was keeping the plot twists and ending a secret. There is a rumor that after getting the rights for the book, he bought up as many copies of the novel as he could to keep the ending a secret. One the first day of shooting all members of the cast and crew had to raise their right hands and promise not to divulge one word of the story. Hitchcock also withheld the ending part of the script from his cast until he needed to shoot it. He tried to mislead moviegoers and newspaper reporters about Mrs. Bates’s true identity, by leaking stories that he was considering such stars as Helen Hayes and Judith Anderson for the part. While this was obviously a ruse, apparently several actresses wrote to Hitchcock requesting auditions. He even had a canvas chair with “Mrs. Bates” written on the back prominently placed and displayed on the set throughout shooting. Norman’s mother was voiced by Paul Jasmin, Virginia Gregg, and Jeanette Nolan. The three voices were thoroughly mixed, with the exception of the last speech, which used only Gregg’s.

Psycho was shot with budget of $806,947.55, with principal photography beginning on November 11, 1959 and ending on February 1, 1960. Nearly the whole film was shot with 50 mm lenses on 35 mm cameras which closely mimics normal human vision, and helped to further involve the audience. The first scene to be shot was the one in which Marion, asleep in her car, is awakened by a highway patrolman. Except the scenes of Marion fleeing Phoenix which were filmed on backroads in Southern California, Psycho was produced on the backlot at Universal Studios. Hitchcock and cinematographer John Russell regularly used two cameras to get most of the shots, rather than resetting to get different angles (a common television practice which was rare for feature films).

One of the best known scenes in cinema history and the film’s pivotal scene is the murder of Janet Leigh’s character in the shower and there are numerous myths and legends surrounding its filming. The “shower scene” was shot from December 17 to December 23, 1959, runs 3 minutes and features 77 different camera angles. The set was built so that any of the walls could be removed, which would allow the camera to get in close from every angle. Originally audiences were to see only the knife wielding hand of the murderer but Hitchcock suggested to Saul Bass, who was storyboarding the sequence, a number of angles which would capture screenwriter Stefano’s description of “an impression of a knife slashing, as if tearing at the very screen, ripping the film.” Interestingly, at the end of the shower scene, the first few seconds of the camera pull back from Leigh’s face is in fact a freeze frame. Hitchcock was required to do this because, while viewing the rushes, his wife noticed the pulse in Leigh’s neck throbbing.

During filming, Janet Leigh wore thin moleskin to cover the most intimate parts of her body in the shower and to help keep her comfortable, Hitchcock kept a closed set. Contrary to a widely told tale, Hitchcock did not arrange for the water to suddenly go ice cold during the scene to elicit an effective scream from Janet Leigh. Leigh said that the crew took great care to keep the water warm, and filming the scene took an entire week. The tale appears to have started with Universal tour guides, who were making up an interesting story to tell tourists as they passed the “Psycho” house on the Universal backlot tour.